Dr Vassilis Adrahtas, Greek City Times

Death is a limit – the ultimate limit – for human existence, and as such becomes a problem which rarely generates an experience of tranquillity and reassurance, but something however that it is more likely to do so in life-worlds of immanence, whereby everything is in some way repeated, perpetuated or preserved as an integral part of the fabric of reality. Things are quite different in the case of life-worlds of transcendence, whereby human agency aspires to go and to be beyond the confines of reality, confronting death as the last frontier.

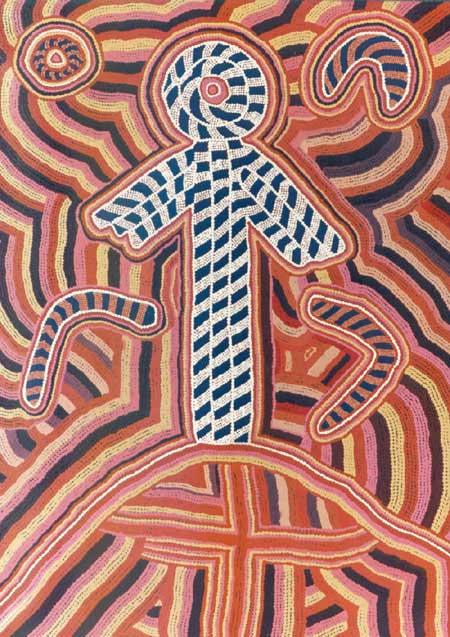

As for Indigenous Australian life-worlds, I would dare say that not only they adhered to the pattern of immanence, but more so they were the last place on earth where someone would look for… the fear of death!

In precolonial times, Indigenous ways of living were perfectly tuned in with Indigenous ways of dying. That is to say that for Indigenous people, death was seen as the most natural aspect of the human condition and the most normal course of things. And how could it be otherwise, when life was experienced as nothing but the incessant rhythm of place/topos from within itself, through its environmental and cultural manifestations into its source again and again and again? And not just as a rhythm, but even more so as a symphony of multiple rhythms transacting and blending with one another. In such a context and understanding death was a sublime moment in the realisation and self-awareness of the Land through the latter’s very own agencies – human and non-human alike.

So, Indigenous life-worlds used to be paradise-like havens or a kind of Eden? Certainly not! They suffered from fundamental problems like any other human life-system. It might not have been sinfulness, as we know it in the Christian tradition, but they had to deal with what could be called topological malfunctioning: the act of any manifestation of the Land, that is, any dreaming, against the overall polyphonic rhythm of place. This malfunctioning was expressed as something going against the Law of the all-encompassing Dreaming, something we could call unlawfulness, whereby even death took on a place and role quite different to what was expected. Imagine now what happened when this inherent – for one reason or another – unlawfulness was bolstered and accelerated by the invasion of White utopia into Black topos. Imagine the monster death was transformed into…

Why Would Resurrection Even Be Needed?

When structural or other serious problems arise in a life-order that is driven by the logic of abidingness, the solution is pretty simple: make things conform to abidingness once again. This is what, basically and primarily, ceremonies and rituals – especially initiatory rituals or rites of passage – are all about: restoring the Law of the Land. In this respect, death is no exception; there is no need to get rid of death, let’s say, by the immortality of a certain individualised manifestation of place/people or even more potently by resurrection. The only thing required is to live out, so to speak, death as an initiation, the ultimate and complete initiation, that allows a certain people to find their place again and secure thus its continuing polyphonic realisation.

But what happens when a problem is not simply structural or even serious? What happens when the problem is the challenge of the Indigenous life-order itself? This is precisely what took place – and is still taking place – with the presence of the White Christian-based worldview of the invaders. Within a century or so, most of the Indigenous topologies were so violently disrupted by the Western utopian life perspective that they virtually went through an unprecedented collective death; a death that, unfortunately, could no longer be rectified through the usual means of the Indigenous life-order, and this simply because it amounted to the death of the life-order itself… This is how the Indigenous peoples started discussing ideas and/or images of immortality, and later on the prospect of resurrection as preached by Christian missionaries.

Resurrection – and not just some general idea about immortality – is the cornerstone of the Christian experience. Especially, in the Orthodox tradition the Resurrection of Jesus takes on a broader signification and becomes the resurrection of humanity and ultimately the resurrection of the entire creation. It is this Resurrection of the God-Man that constitutes the restoration of humanity after the Fall, and at the same time the solution to the problem of death. And it is well-known theologically that death is the end result of the Fall. But could this be relevant in an Indigenous Australia context? I truly believe that it could, if only we would realise that the experiential equivalent to the Fall came with the invasion, and that death is virtually the disconnection from the Dreaming…

Towards an Indigenous Theology of the Resurrection

Precolonial and postcolonial Indigenous Australia are undoubtedly the same thing, but equally undoubtedly their continuity has been severely broken. The discontinuity effected via the White Christian invasion does not resemble in anything the everyday or occasional or even more challenging discontinuities that every life-world must struggle with. This is a discontinuity of cosmic or, better, Dreaming proportions. It is the very core of Indigeneity that has been hit, undermined and affected. Initiations have been reinvented and reapplied to the new conditions, while they have been more or less creatively effective in restoring the order of things. But not in all cases, not for all people… It seems that for some restoration cannot come any longer through the familiar immanent channels of repetition, perpetuation and preservation of Indigeneity. It seems that for some death not only is not the ultimate solution anymore, but all the more the ultimate obstacle they have to overcome. In the context of their experience, only a Resurrection can restore things, that is, the Resurrection of Jesus with all its universal and cosmic implications can now be envisaged by Indigenous peoples as the way out of the ‘valley of death’…

Due to the White disruption of the Dreaming, not only Black topos was taken over by White utopia, but also the Indigenous individual emerged as a socio-historical phenomenon. To a great extent, this type of individuality is a ramification of the huge existential problem that came with the destruction of the inherent link between Indigenous peoples and their places. To put it otherwise, individuality comes out of this unprecedented crisis as a response to the latter; the Indigenous individual becomes now the voice of mourning and loss, and at the same time the determination for reclaiming and re-empowerment. But, at the end of the day, individual death runs against all this. Only a Resurrection, the Resurrection of Jesus as the true and perfect Individual can allow for the Indigenous individual to be sustained, not just in perpetuity, but in eternity!

To be sure, the perpetuity of the Indigenous individual in eternity through the Resurrection of Jesus is the most potent change and transformation that Indigenous abidingness has ever experienced or could wish for. But now that the Land has been claimed by others; now that the Indigenous peoples have become individual cries; now that death can no longer secure the rhythm of life, only the prospect of a Resurrection of the Land, of the individual and of life in general can bring about restoration and, even more, a New Dreaming, a Dreaming of true reconciliation and justice. But this is a yearning one should fight for precisely because it can be witnessed in the person and life-story of God Himself. In the prospect of such an Indigenous theology of Resurrection, I truly believe that Orthodoxy has much to offer and at the same time much to benefit from…

ABOUT | INSIGHTS INTO GLOBAL ORTHODOXY with

"Insights into Global Orthodoxy" is a weekly column that features opinion articles that on the one hand capture the pulse of global Orthodoxy from the perspective of local sensitivities, needs and/or limitations, and on the other hand delve into the local pragmatics and significance of Orthodoxy in light of global trends and prerogatives.

Dr Vassilis Adrahtas holds a PhD in Studies in Religion (USyd) and a PhD in the Sociology of Religion (Panteion). He has taught at several universities in Australia and overseas. Since 2015 he has been teaching ancient Greek Religion and Myth at the University of New South Wales and Islamic Studies at Western Sydney University. He has published ten books. He has extensive experience in the print media as editor-in-chief, and columnist, and for a while he worked as a radio producer. He lives in Sydney, Australia, his birthplace.

Δεν υπάρχουν σχόλια:

Δημοσίευση σχολίου

Σημείωση: Μόνο ένα μέλος αυτού του ιστολογίου μπορεί να αναρτήσει σχόλιο.