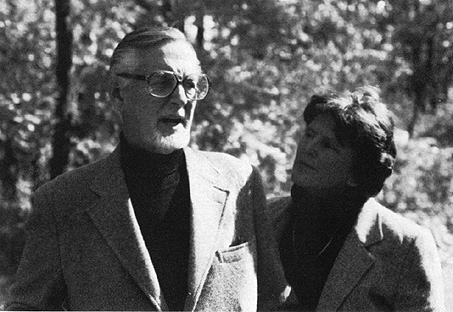

Father Alexander (center) with Matushka Juliana (left) and Alexander Solzhenitsyn (right),

winner of a Nobel Prize for Literature.

John A. Jillions, wheel

INTRODUCTION

Fr Alexander Schmemann died in 1983, long before the resurgence of the Orthodox Churches in Eastern Europe could be realistically imagined with what this might mean for the emergence of a powerful Orthodox voice worldwide. Today global Orthodoxy is more free than it has been in centuries and—despite continuing divisions—has the ability to start coming together to find and speak its own voice, as the Holy and Great Council in Crete 2016 at least haltingly demonstrated. But this begs the question: what message will this new and potentially muscular Orthodoxy bring to the world?

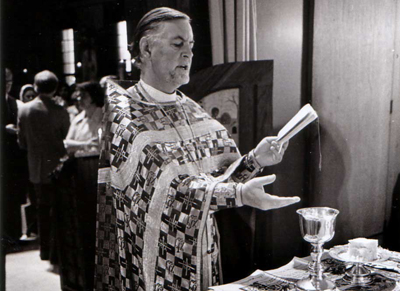

Schmemann (1921–1983), the longtime Dean of St Vladimir’s Seminary in New York, was one of the leading Orthodox theologians of the 20th century and had a profound effect on liturgical theology and its lived expression across the Orthodox and wider Christian world. His writing, his teaching, his liturgical celebration, his sermons, his conversations and his presence had deep influence on so many people, especially his thousands of students, of whom I am blessed to be one (I studied at St Vladimir’s Seminary 1977–80.)

For ten years before his death he kept a personal journal that was later translated, edited and published by his wife, Juliana Schmemann, as The Journals of Alexander Schmemann, 1973–1983 (Crestwood, NY: St Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 2000.) As his journals reveal, Schmemann deeply loved and was shaped by his experience of the Orthodox Church—but he was also deeply critical. While he was a masterful observer and critic of Western society and Western Christianity, he reserved his most trenchant critique for the Church he knew best. And in this, as Vigen Guroian has said, Schmemann was “undoubtedly the harshest self-critic among Orthodox theologians.”[1] Schmemann’s fundamental criticism was that Orthodoxy had become an idol to itself. It had thus eclipsed Christ. And because of its allergy to self-criticism, Orthodoxy had become incapable of seeing, admitting and repenting of its fault. The Orthodox Church will fall short of the joyful eschatological vision of the Gospels until it puts the idol of Orthodoxy to death.

Part I of this essay will examine Schmemann’s journals for the various streams of his critique and argue that the doubts, criticisms and questions Schmemann first raised privately many years ago still need serious public attention as Orthodoxy seeks to find its voice, message and mission in the 21st century. However, if Fr Alexander’s vocation as a prophet (though he himself would have eschewed that title) led him to speak clearly, convincingly and critically about the realities he saw, he was much more ambivalent about proposing solutions. Without attempting to guess what his solutions might be today, in Part II of this essay I will suggest that Fr Alexander’s sharp critique can be channeled into positive terms by refocusing the Orthodox Church on Christ as scriptural, contemplative and self-emptying.

SCHMEMANN’S CRITIQUE OF ORTHODOXY

The title of this essay is taken from Schmemann’s journal entry for November 26, 1973: “‘Little children, keep yourselves from idols!’ (1 John 5:21). Sometimes I see Orthodoxy in a thicket of idols. To be attached to the past always leads to idolatry, and I see many people living by the past, or rather, by many pasts.” [2] This is a theme that is repeated relentlessly throughout the journals. In February 1977 he writes:

I realize how spiritually tired I am of all this “Orthodoxism,” of all the fuss with Byzantium, Russia, way of life, spirituality, church affairs, piety, of all these rattles. I do not like any of them, and the more I think about the meaning of Christianity, the more it all seems alien to me. It literally obscures Christ, pushes him into the background (146).

And yet such self-criticism finds no place for consideration in Orthodoxy. Schmemann’s key contention is that the very notion of self-criticism is simply absent from historic Orthodoxy.

An Orthodox person will not say, will not acknowledge that Orthodoxy can be decadent, that a great part of the heavy volumes of the liturgical Menaion consists of imitative and often meaningless rhetoric. An Orthodox person will condemn that very thought as heretical and sinful (315).

Without this faculty of self-criticism change is impossible. “To change the atmosphere of Orthodoxy,” he says, “one has to learn to look at oneself in perspective, to repent, and, if needed, to accept change, conversion. But in historic Orthodoxy, there is a total absence of criteria of self-criticism” (47). Accompanying this absence of self-criticism is a “denial of any reason, logos, analysis” (192), and a “deadening of thought and vision” (329) that have produced lamentable immobility, narrow mindedness and provincialism. The church is perpetually looking backward to a mythic past rather than forward to the coming of Christ and his Kingdom, and this has robbed Orthodoxy of its original eschatological vision. Instead of living the tension between history and eschatology, argues Schmemann, Orthodoxy has settled comfortably for “hopelessly Constantinian” Byzantine and Slavic worlds that substituted spirituality for Christ (208). “What happened was the reduction of the Church to a mysterious piety, the dying of its eschatological essence and mission, and finally the de-Christianization of this world and its secularization” (317). By taking the focus away from Christ, says Schmemann, church life itself was turned into an idol and became sin. “The depth and the newness of that sin is that the idol is the Church, the services, theology, piety, religion itself. It sounds like a cheap paradox, but the Church is most harmed and hindered by the Church itself, Orthodoxy by Orthodoxy, Christian life by piety, etc.” (167).

Time and again, Schmemann points to the triumphalism, arrogance and pride of Orthodoxy, especially vis à vis the Christian West. This is a theme that appears regularly in Schmemann’s writing, as Vigen Guroian points out.

On the one hand, Orthodox triumphalistically claimed exclusive possession of the ancient tradition. On the other hand, the consciousness and behavior of the Orthodox Christians belied this claim and showed them every bit as compromised to secularism as the Western forms of Christianity that they criticized.[3]

This triumphalism would be more irritating if it wasn’t so ridiculously out of touch with reality. Schmemann on a few occasions hints at the comic absurdity of the Byzantine picture of Orthodoxy, especially as it is displayed in the West, with its vestments, awards, titles and jockeying for honor. It is comical, he says, “but nobody laughs” (330).

In the East, people are often devoid of any sense of humor; therefore they are often pompous, proud, prone to dramatize. I am always sad when meeting people without humor, often tense, easily offended. If we have to “be like children,” it is impossible to do so without laughter. But laughter fell and can also be demonic. In dealing with “idols,” however, laughter is salutary, since it allows us to see them in perspective (22).

Once the church becomes an idol, it is subject to a bewildering array of temptations. I found six broad sets of these temptations in Schmemann’s Journals.[4]

1. Self-infatuation, pride and arrogance

The goal of the Church has become the Church itself, its organization, its welfare, its success! (329).

2. Preoccupation with honor and rights

It is frightening to think that in some sense, the Church also lives with pride—“the rights of the churches,” “the rights of the Ecumenical Throne,” “the dignity of the Russian Church,” etc., and a flood of joyless, complicated and fearful “spirituality.” It is a continuous self-destruction (161).

3. Triumph of self-enclosed traditions that exclude the possibility of anything new

Whether it’s Russians, Carpatho-Russians, Greeks, Arabs, Albanians, Serbians or Romanians, there stands between them and Orthodoxy (their own faith) a sort of wall, impossible to breach with preaching, books, or any religious educational activity. And it is so because this wall essentially represents their perception of the Church (already existing for centuries), of liturgical services, of spirituality, of faith itself. It is not only emptiness, an absence of knowledge or interest. No. It is a kind of fullness beyond measure, forbidding any intrusion into their conscience of anything new (326).

4. A psychological style that promotes a religion of joyless “falsity and fear” (294), escape and indifference to the world

Byzantium’s complete indifference to the world is astounding. The drama of Orthodoxy: we did not have a Renaissance, sinful but liberating from the sacred. So we live in nonexistent worlds: In Byzantium, in Rus, wherever, but not in our own time (213).

5. Loss of childlike simplicity and directness in liturgical life, human relations and church order (155, 181, 253)

How torturous is the ‘churchly’ language that one must speak in church— the tone, style, habit. It is all artificial; there is a total absence of simple human language. With what a sigh of relief one leaves the world of cassocks, hand-kissing and church gossip (254).

6. Clericalism (310), a “bachanalia of sacred ‘things’” (273), a monastic “vaudeville of klobuks, cowls, stylization, etc.” (284)

I feel like running away from this kind of Orthodoxy with all its cassocks, headwear, pointless ceremonies, unctuousness and slyness; to be myself, not to play some artificial, archaic, dull role (304).

Schmemann is especially distressed that these pathologies so easily infect newcomers to the Orthodox Church. Here he comments on a recent convert:

Why is it that the closer he came into contact with Orthodoxy, the stronger was his longing for this dark, strange fanaticism, for accusations and cursing? If only he was the only one, but it happens with so many converts and also with so many cradle Orthodox people who fall into ‘acute churchliness.’ Is it a reaction against the minimalism of the Church, of parishes? At some point they begin to hate the light and the joy of that faith, and it is so frightening (320).

In spite of these damning observations, it would be a mistake to read Schmemann’s journals through this lens alone. Indeed, just ten days before he wrote that entry about the “thicket of idols” he wrote about being “elated” by the Pittsburgh “All-American Council” in November 1973, the bi-annual gathering of about 1000 bishops, clergy and laity from across North America.

I went to the council quite downcast and with a lack of any enthusiasm, not expecting much. After three days of incredible effort and tension (I was chairman again) suddenly it became quite clear: Our Church is alive in spite of everything, and an assembly of rather “little” people is transfigured into the Church. Wonderful prayer services. Hundreds of communicants and, mainly, a kind of common inspiration. I still feel elated by the Council. The miracle of the Holy Spirit in an American Hilton Hotel! (18)

It would also be a mistake to read Schmemann’s critique as a rebellion against hierarchy. While being critical of so many aspects of contemporary Orthodoxy, Schmemann repeatedly rejects rebellion as a valid modus operandi in the Church. He spent much of his career working closely with bishops—and arguing with them—but he says, “I believe in bishops with the same faith I believe in the Church,” because bishops, in their essential conservatism, preserve the patient and careful discernment of spirits the Church needs in every age (152).

Schmemann’s journals are dotted with experiences of parishes, people and church life that re-inspire him, despite the idols he sees and fights against. After the Memorial Day celebrations at St Tikhon’s Monastery in May 1977 he wrote:

I thought again that I am at home in the Church, although so often in doubt about churchly details….As ailing as the Church is, as coarse, as worldly as church life has become; no matter how much the solely human, too human triumphs in the Church— only through the Church can one see the light of the Kingdom of God. But one can see that light and rejoice in it only inasmuch as one denies one’s self, liberates one’s self from pride, from narrowness and constraint (170).

In spite of its flaws, the miracle, says Schmemann, is that the historic Orthodox Church has preserved enough authentic life, especially in its liturgy, to be a source of wonder and joy. “Once more, I am convinced that I am quite alienated from Byzantium, and even hostile to it. What is surprising is that the Byzantine Liturgy basically withstood and endured this stuffiness and did not let it into the ‘Holy of Holies’”(213). But this also means that the Orthodox Church is leading two contradictory lives. “I have the feeling that in Orthodoxy (i.e., in Christianity) two religions coexist in many ways opposites of each other. The religion of Christ—fulfilled in the Church, and the religion of the Church, or simply religion” (172).

CONSTRUCTIVE WAYS TO ADDRESS SCHMEMANN’S CRITIQUE?

If Fr Alexander is bitingly clear about the critique, what about his solutions? While he felt that the Orthodox Church in history had largely lost its ability to be a prophetic voice for Christ, how this might be restored to address specific issues even he could not say precisely. For example, he felt that the Orthodox tendency to turn all church history into sacred history was problematic but he felt torn between historians and pastors and could offer no solution.

There is something there that needs to be corrected, but how? I do not know. On one hand I agree with historians, since without a historical perspective, there would be false absolutisms. On the other hand, I agree with those of the pastoral group who tend to limit history for the sake of a real, live, existing Church (53).

On many questions he was ambivalent and unprepared to give solutions. “Everybody around me seems to know so clearly what is needed; they are all goal-oriented, while I always have the feeling that I really do not know what, where, why…” (52). Schmemann’s journals are full of unanswered questions that he poses to himself, and there is no clearly thought-out scheme to address the issues he raises. As Vigen Guroian reports, Schmemann was not sure whether the Orthodox Church would be prepared to handle the break up of secularism either in the West or in the East. At least on one occasion, “Schmemann wondered out loud whether the church would be prepared to answer the genuine religious needs of modern people in the breach as they searched for something to believe in and hope for after the collapse of secularism’s ‘religious’ hegemony.”[5]

What does emerge from Schmemann’s journals is a single test to judge all church life: faithfulness to Christ. Is this or that dimension of church activity—its parishes, dioceses, monasteries, seminaries, jurisdictions, patriarchates, missions, boards, departments, commissions and institutions—making known Christ, as He is encountered in the catholic fullness of the Orthodox faith? If not, it has lost its prophetic voice and is bound by the “‘shell’ of tradition.”

Prophecy must be about Christ; not about Jesus, not about religious revival, not about prayer and spirituality, but about Christ, as he is revealed in the genuinely Catholic, genuinely Orthodox faith…. Not return to the Fathers or Hellenism, but in a way, the overcoming of the whole ‘shell’ of tradition—the opening, the rediscovery of Truth itself, as given to us in Christ (165).

It’s uncertain what the implications of “overcoming the whole ‘shell’ of tradition” would look like to Fr Alexander. It would have been interesting to see—had he lived longer—if he would have had the ability to publicly verbalize more about what this meant to him. But in the end, what we are left with is his insightful diagnosis and a very broad treatment plan.

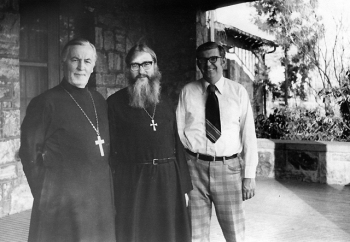

Father Alexander (left) with (now) Metropolitan Kallistos Ware (center) and Dr David Drillock (right).

I am not trying to summarize Fr Alexander’s lifetime of writing or his journals. Nor do I pretend to imagine what prescriptions he might have proposed had he lived into our own times and temptations. But using his observations as the foundation I simply offer three ways that his prophetic hope for Church life could be put into practice: by focusing on the scriptural Christ, the contemplative Christ and the self-emptying Christ.

The scriptural Christ

“In the Bible,” wrote Schmemann, “there is space and air; in Byzantium the air is always stuffy” (213). It is this biblical music that Schmemann hears as the “the melody of Orthodoxy, precisely never stifling, but joyful, light, free” (199). While his writings are permeated with the spirit of the Gospels, this somehow did not translate into the liturgical emphasis that is associated with his name. He was partly responsible for this. Certainly the focus of seminary education came through the lens of worship, not primarily the Scriptures. For Fr Alexander, liturgy was life in its fullest sense and encompassed everything about life in Christ expressed in the Scriptures. But Orthodox clergy and parishes are much more likely to stress the need for full liturgical schedules than personal familiarity with Christ who reveals himself through the scriptures.

In 2010 my wife and I had the great blessing to stay in Labelle, Quebec for a few days in late summer, where the Schmemanns have a summer cottage and we had some insightful conversations with Juliana Schmemann, who reposed in January 2017. She shared Fr Alexander’s view “that Orthodoxy has become detached from the Gospel, from Christ. He is the One who is the center, whose suffering and crucifixion on our behalf must be at the heart of faith. I wonder if we haven’t become detached from that. Too much church and not enough Gospel.”

The contemplative Christ

In other conversations with Juliana Schmemann she said that one of the most spiritually satisfying places she had encountered was the community of nuns at the Orthodox Monastery of the Transfiguration in Ellwood City, Pennsylvania. “It’s a piece of paradise for me,” she said. I was surprised how warmly she spoke of the monastery because it seemed to contrast with Fr Alexander’s apparent skepticism about monastics. “No,” she said, “That’s a mistaken impression that many have. Father was not against monasticism, or confession, but he was against how it was manifested. He would have loved the nuns.” Indeed, Fr Alexander appreciated the authentic monasticism he encountered among the Copts in Egypt during a visit in 1978.

I had an extraordinary day: a visit in the desert to three monasteries with an uninterrupted tradition from Anthony the Great, Makarios etc…And the most amazing, of course, is how very much alive it all is: Real monks! In my whole life, I have seen only imitations, only playing at monastic life, false, stylized; and mostly unrestrained idle talk about monasticism and spirituality. And here are they, in a real desert. A real, heroic feat (189).

Juliana said there was a deeply contemplative side to Fr Alexander. During summers in Labelle he would work at the dining table early in the morning, looking out over the lake. “When he would hit a rough spot in his writing he would go out onto the porch and walk back and forth. At those times he would tell me, ‘I have to go to the white rock, do belogo kamnya.’ It was a reference I never understood.”

Perhaps there’s not much to this. Maybe Fr Alexander was simply referring to a favorite white inspirational rock up there in Labelle that he needed to see or touch. But to me, it could well be a reference to Revelation 2:17: “ ‘To him who conquers I will give some of the hidden manna, and I will give him a white stone, with a new name written on the stone which no one knows except him who receives it.’” The journals reveal this prayerful, hidden, contemplative dimension of Fr Alexander on every page. But it is also no accident that Mary, the Mother of God, the one who “kept all these things, pondering them in her heart” (Luke 2:19) was the subject of some of Fr Alexander’s most profound reflections.[6]

The self-emptying Christ

Juliana Schmemann said that Fr Alexander was one of most self-giving and kindest people she ever knew. “That made it difficult sometimes for others because he would not make any harsh decisions.” At the same time, he spent himself completely and worked endless hours— teaching, seminary administration, liturgical services, confessions, counseling, church committees and consulting, writing books, his weekly broadcasts on Radio Liberty (two each week, for thirty years). Still, she said, “one of his constant preoccupations was the sense that he was not doing enough for the Lord. He would have made a wonderful martyr!”

What I draw from Fr Schmemann’s example is this: if the besetting sin of the Orthodox Church is self-idolatry, then the cure is its opposite: self-emptying for the sake of others, to become a servant church, emptying itself for the life of the world. Many have written about the special place of “kenoticism” in Orthodoxy, but Fr Alexander took this a step further to link kenosis with the voluntary shedding of ecclesial pride. In his journal entry for November 18, 1974 he wrote, “On the eve of the Christmas fast, we are trying to preach to the students why the coming of God into the world in the form of a small child is not only a kenosis—a self-emptying of divinity—but the most adequate revelation of God. In that Child there is no need for strength, glory, “rights,” self-affirmation, authority or power” (55–56). Earlier in that same entry he wrote, “Christians are the first to live with pride, self-affirmation and the need to expand. Where can repentance come from, or self-limitation? ‘I’ might give in, but ‘we’ will never give in because ‘we’ are right—always right; could not live a minute without our ‘right’" (55).

CONCLUSION

I’ve looked briefly at Alexander Schmemann’s extensive critique of Orthodoxy and considered some possible avenues for re-imagining how the Orthodox —now facing the real possibility of a new and powerful stage in our history— could refocus Church life on Christ in the scriptural, contemplative and self-emptying ways that cut through the “thicket of idols.” Still, even these would be half-measures. In Fr Alexander’s eschatological vision of the Kingdom of God only the death of Christianity as we know it can triumph over its destructive inner forces.

The ‘death of Christianity!’ It sounds horrible. But is it so? It constantly seems to me (and gives me inner light and joy) that the death of Christianity is needed, so that Christ would be resurrected. The deadly weakness of Christianity lies in only one thing—forgetting and neglecting Christ. In the Gospel, Christ always says “I”—He says about Himself that he will come back in glory, as a king. One must love Him, expect Him, rejoice in Him and about Him. When nothing of Christianity will remain, only Christ will be visible; and neither revolution, nor Islam, nor hedonism will have any power left. Now is the time for the prayer, ‘Come, Lord Jesus…! (212)

But this dark conclusion should not be misunderstood. As Juliana Schmemann said, “He was a builder rather than a destructive force, and a preacher of what Church is and could be, if the Gospel were again an integral part of Church life in every detail.” Fr Alexander did not want to be boxed in by his critique of Orthodoxy or labeled as a “prophet” or “radical reformer,” any more than he wanted to be labeled a “traditionalist.” Instead he was committed to the unfinished, open character of the Church as life in Christ.

I realized how difficult it is for me ever to be wholly in one camp. In all that I love and consider mine—the Church, religion, the world where I grew up and to which I belong, I often see deficiencies and lack of truth. In all that I do not like— radical ideas and convictions—I see what is right, even if relatively right. Within religion I feel stifled, and I feel myself a radical “challenger.” But among challengers I feel myself conservative and traditionalist. I cannot identify with any complete system with an integral world or an ideology. It seems to me that anything finished, complete and not open to another dimension is heavy and self- destructive. I see the error of any dialectics that proceed with thesis, antithesis and synthesis, removing possible contradictions. I think that openness must always remain; it is faith, in it God is found, who is not a “synthesis,” but life and fullness (46).

Fr Alexander’s legacy would be meaningless if he were only a cranky, bitter critic. Those who know the full range of his writing know the joy and brightness of his eschatological vision. But it is precisely his love for Christ and the Church that gives the sharpness of his critique so much weight. Given the state of world Orthodoxy, and its persistent and growing triumphalism, it seems to me that Fr Alexander’s ability to see through the “thicket of idols” is especially valuable today, and a comfort to those who might otherwise despair.

This essay will appear in a forthcoming issue of The Wheel dedicated to assessing the legacy of Father Alexander Schmemann. Make sure you don't miss an issue of The Wheel, by subscribing today in print or online.

The Very Rev. Dr. John A. Jillions is chancellor of the Orthodox Church in America and an associate professor of religion and culture at St. Vladimir’s Seminary. He holds a DMin from St. Vladimir’s and a PhD in New Testament from the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki. He was a founding principal of the Institute for Orthodox Christian Studies in Cambridge (UK) and was an associate professor of theology at the Sheptytsky Institute for Eastern Christian Studies in Ottawa (now in Toronto). He has served parishes in Australia, Greece, England, Canada, and the United States.

References

[1] Vigen Guroian, “An Orthodox View of Orthodoxy and Heresy: an Appreciation of Fr Alexander Schmemann,” Pro Ecclesia IV:1 Winter 1995), 86.

[2] The Journals of Alexander Schmemann, 1973–1983, trans. Juliana Schmemann (Crestwood, NY: St Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 2000), 18. Subsequent references to the Journals cite the page numbers in the body of the text.

[3] Guroian, 81.

[4] The cited page numbers below are just examples; many more could be added.

[5] Guroian, 86.

[6] See for example Alexander Schmemann, The Virgin Mary, Celebration of Fait 3 (Crestwood, NY: St Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 2002, revised edition).

Further Reading

Sergius Bulgakov, The Bride of the Lamb, trans. Boris Jakim (Grand Rapids/Edinburgh: Eerdmanns/T & T Clark, 2002) [original, 1945].

Vigen Guroian, “An Orthodox View of Orthodoxy and Heresy: an Appreciation of Fr Alexander Schmemann,” Pro Ecclesia IV:1 (Winter 1995).

Alexander Schmemann, Church, World, Mission (Crestwood, NY: SVS Press, 1979).

Alexander Schmemann, The Journals of Alexander Schmemann, 1973-1983, ed. & trans. Juliana Schmemann (Crestwood, NY: St Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 2000).

12 Likes

Share