Dr Vassilis Adrahtas holds a PhD in Studies in Religion (USyd) and a PhD in the Sociology of Religion (Panteion ) in Greek City Times

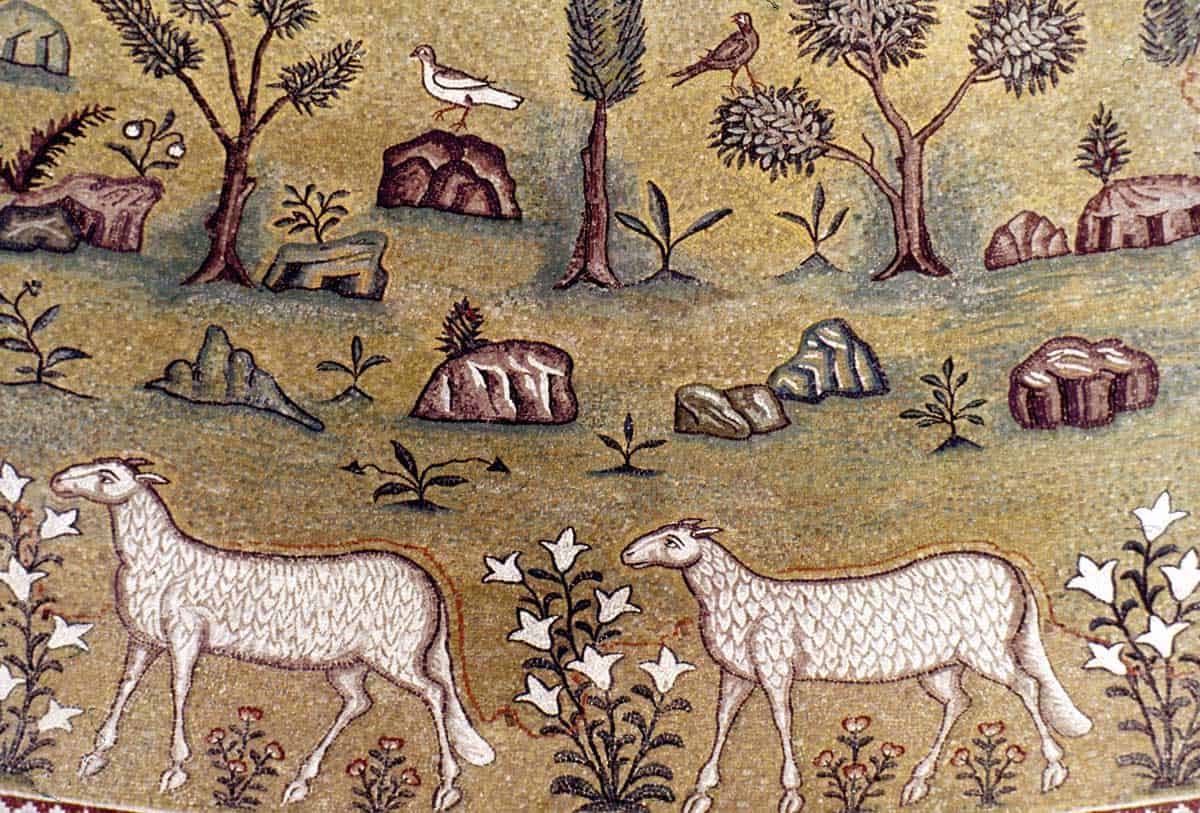

“God saw everything that he had made and indeed it was very good” (Gen. 1:31).

Let's be honest now: Does it get greener than that? I don’t think so! But then, how come nowadays everyone feels the dread of climate change? Why have we reached a point where the natural environment faces its own melting down? I suppose something must have gone really mad … and bad … and someone is still not taking responsibility for their actions … Instead, the new mantra is to talk and to keep on talking “green”, “eco”, “sustainable”, “environmentally friendly” … Conference upon conference, publication upon publication, policy upon policy, thinker upon thinker, the planet is being reassured of its salvation, especially since theology has entered the game in the guise of “green theology” or “eco-theology”. But let’s be honest again: can theology just step into the room and pretend to be innocent, to hold the much-needed key to the solution, to be the censor of what has been going on throughout history? I don’t think so! And what about Orthodox theology? Has it ever been green? Can it possibly be green? Is it green enough?

Theology turns into eco-theology by reiterating some of its most well-known premises from the past: the affirmation of Creation as intrinsically good and the duty of stewardship bestowed upon humankind. In turn, Orthodox theology joins in and along these same lines repeats some of its traditional axioms: the ascetic ethos of its spirituality, the eucharistic use of the world and of course the latter’s doxological offering to God … All this is further embellished with a general condemnation of avarice and a rather vague mentioning of selfish financial interests … And as of late, what we have been witnessing in the Orthodox Church is the popping up of so-called “green parishes” – presumably as a practical implementation that most likely is supposed to counterbalance the one-sidedness of wishful theologising. But is this enough? Is this even relevant to a problem that is so conspicuously modern? And if all this was already there, informing and guiding the collective consciousness and praxis of generations, why didn’t it make any difference? And how are we to expect that it will manage to do so now? My suspicion is that Orthodox theology has not even started discerning the gist or the real dimensions of the problem, but is simply repeating in its own jargon what is taken to be politically correct …

If Creation, that is, the natural order, is intrinsically good, what are we to say about the techno-scientific, that is, the human-made order? Since the latter is essentially based on the former, is it intrinsically good as well? What’s the place of humans in the whole equation? At this point one could say that there seems to be a certain dysfunctionality, a malfunction concerning the human stewarding of nature – in other words, the human use of nature through technology and science. But can this dysfunctional use be overcome by only the ascetic ethos? I firmly believe that it can. However, this ethos must be reinvented and not just cherry-piked out of some authoritative tradition, as if the latter had in mind the greenhouse effect, climate change or the depletion of natural resources, and so forth. Equally so, the Eucharist and doxology as privileged hierophanic modes of Christian being have to find a way to penetrate the everyday secular way of living, in order to signify and at the same time trigger developments that can make the techno-scientific more natural and the natural more techno-scientific. This would indeed be a revolutionary metabole (what in Latin is grossly termed transubstantiatio) and a most pertinent mystagogia (and not simply a thanksgiving à la americana).

The ecological disaster we are experiencing is basically and primarily a problem of the techno-scientific world we are living in. In this respect, if Orthodox theology truly wants to go green and be eco-minded, it should start focusing not on nature – which, to be sure, is an abstraction or a kind of secondary substance as Aristotle would say – but on technology and science, that is, on the very concrete and primary ways that inform and transform our actual everyday lives into insatiably devouring mechanisms. To imbue the quotidian – which is virtually the secular but, in some respects, also the religious – with the spirit of metabole and mystagogia amounts to something more than just a shift in personal spirituality or individual morals; it literally demands a political intervention and a collective mobilisation. Whenever Orthodox theologians condemn avarice and refer to selfish financial interests, they should stop treating them as if they were thin air – they do have a name and a shape and a “face”. General avarice and vague interests are but the unspoken metonymies of capitalism and, for that matter, neo-liberal politics and priorities in all spheres of life on our planet.

Ok, spirituality is good, and self-control is also good, and the belief in God’s good creation is even better. But they are not enough; not enough to define our duty of stewardship that consists in the metabole and the mystagogia of the worldly, so that the latter may embody and reflect the Age-to-Come, “a new heaven and a new earth” (Rev. 21:1). This vision of the great Utopia of the Holy Trinity can never be accomplished by us alone in this time and age we call history; hence, the destruction of the abundance of life in all its forms and the fundamental inadequacy of artificial or virtual or techno-intelligent reality will always be the lot of the human condition. So how does one become green considering this inescapable predicament? Does it even matter to become green? Yes, it does! And there is a way to become not just green, but radically green! Orthodox theology should stop being a follower of a culture that suddenly is afraid of its own extinction and therefore wants to save the planet, not out of some loving duty but out of mere self-preservation. Orthodox theology should prove itself as a prophetic pathfinder that, instead of promoting new capitalist prospects of eco-friendly technologies at the parish level, chooses to irrupt into the public space and everyday practices via a potent political aesthetic: the symbols of an integral and harmonious techno-nature!

The closest that Orthodox theology got to the theoretical articulation of these symbols was in the work of Fr Sergei Bulgakov. This controversial, yet ingenious Russian theologian, opened our eyes to both God-made and human-made creation as a result and bearer of Sophia, Divine Wisdom. For him to acknowledge something as created – either at the natural or the cultural/technological level – is one side of the coin we call Divine Revelation; the other side being that of the Uncreated! Thus, if the created and the Uncreated are sides of the same coin, this means that nature and the techno-scientific are shades of the same colour, shades that can and should become our stairways to Heaven. Saying “yes” to technology is saying “yes” to nature, but this “yes” is a big “no” to capitalism, especially its destructively all-devouring neo-liberalist version. In other words, one can only go radically green not by returning to some supposedly lost pristine nature, but by cherishing the mystagogic metabole of nature into an everyday lived-out aesthetics of a more-than-nature reality …

When Orthodox theology grows up in terms of its ecological sensitivities and conceptualisations, then it will probably be able to set forth a human technology and science that respect the integrity of God’s nature by living out their interrelationship and transaction as art; an art not on canvases and other sorts of materials but “in [our] midst” (Luke 17:21). Then it will perhaps be in a position to point radically to a mode of being green that is greener than the green!

ABOUT | INSIGHTS INTO GLOBAL ORTHODOXY with Dr Vassilis Adrahtas

"Insights into Global Orthodoxy" is a weekly column that features opinion articles that on the one hand capture the pulse of global Orthodoxy from the perspective of local sensitivities, needs and/or limitations, and on the other hand delve into the local pragmatics and significance of Orthodoxy in light of global trends and prerogatives.

Dr Vassilis Adrahtas holds a PhD in Studies in Religion (USyd) and a PhD in the Sociology of Religion (Panteion. He has taught at several universities in Australia and overseas. Since 2015 he has been teaching ancient Greek Religion and Myth at the University of New South Wales and Islamic Studies at Western Sydney University. He has published ten books. He has extensive experience in the print media as editor-in-chief, and columnist, and for a while he worked as a radio producer. He lives in Sydney, Australia, his birthplace.

Δεν υπάρχουν σχόλια:

Δημοσίευση σχολίου

Σημείωση: Μόνο ένα μέλος αυτού του ιστολογίου μπορεί να αναρτήσει σχόλιο.