Dr Vassilis Adrahtas holds a PhD in Studies in Religion (USyd) and a PhD in the Sociology of Religion (Panteion), greek city times

Some days ago, I friend of mine asked me in all sincerity: “Do you believe we will see a female priest in our lifetime within the Orthodox Church?” In a very natural way, so to speak, and rather instinctively I replied: ‘I don’t know about female priests, but I am pretty sure that we will see female deacons. We will definitely witness deaconesses in the Orthodox Church as it has been part of our tradition for centuries. It was never abolished but the practice ceased around the 12th century or so. Now is the time for its revival.’

After that I was bombarded with dozens questions of ‘what’, ‘when’, ‘where’ and ‘why’, embarking on a journey of historical theology and liturgics, while my friend was driving me back home. What was surprising though for me, was not the question per se – for the Orthodox faithful, especially in the Diaspora, have witnessed the presence of female Christian clerics for decades now – but the reaction of my friend, that is, his delight to hear that in the Orthodox Church we have more or less solved the whole issue. But then I thought to myself: ‘Have we?’

The Force Stopping The Orthodox Church

It is well known that in the Christian world the ordination of women is already a reality in many Protestant denominations, where there are not only female deacons but also priests and even bishops. The Roman Catholic Church is still in the early stages of exploring the possibilities of ordaining women to the diaconate, while the Eastern Orthodox Church and the Oriental Orthodox Churches are either reluctant or openly against the idea of the ordination of women.

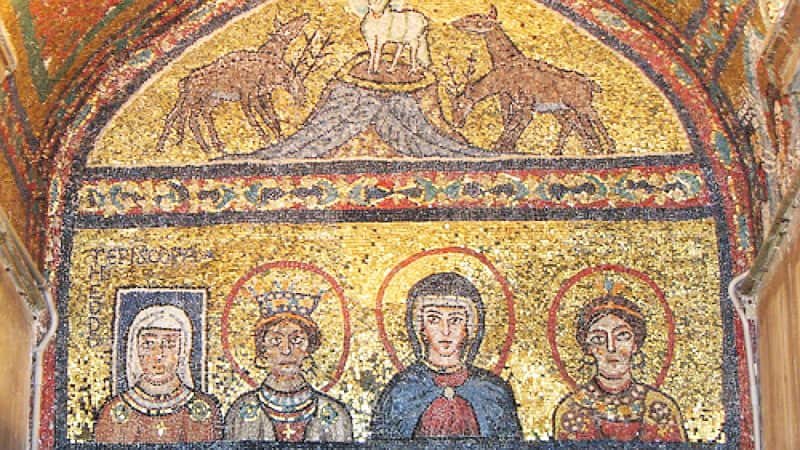

For the contemporary Orthodox Church, the whole discussion started some decades ago and is still ongoing. Although there is a consensus about the traditional character of the order of deaconesses; although there are saints like St Nektarios of Aegina who ordained deaconesses in the early 20th century; although today there are nuns ordained as deaconesses in monastic environments, deaconesses as a tradition have not been reinstated and the future prospects of that changing are relatively small.

One wonders why that is the case, but the answer – if we want to be honest - is one and only: fear!

The leadership of the Orthodox Church, although aware of the tradition, has opted to appease the conservatives within its ranks. But we do know that ‘perfect love drives out fear’ (1 John 4:18) – in other words, we have a deficiency in love …

This deficiency in love is deep-rooted in many respects within the life of the Orthodox Church when it comes to the everyday belittlement of women and everything female. And this has become so endemic that people regard it as part of Church tradition, whereby gender discrimination unfortunately takes on the proportions of divine law! Nothing, however, could be further from the truth of the Spirit than this conservative mentality. Here I must emphasise two things before proceeding: firstly, whatever the reasons the traditional order of deaconesses stopped, these reasons are not valid anymore; and, secondly, whatever might have been the case as to females in priesthood and the bishopric in early Christianity, the Orthodox tradition of ordination developed in a certain male-friendly way, without this entailing that the tradition cannot or should not be enriched and broadened in an additional – this time, female-friendly – manner. To put it differently, I start from the assumption that the era that necessitated the ceasing of an age-long tradition is well over and no longer relevant, and also that the theological discussion of women’s ordination should not refer to the existing orders of presbyter and bishop but should refer to the introduction and development of new orders of ministry in relation to new needs in the life of the Church.

The Future Role and Services of Ordained Women

It goes without saying that the Orthodox Church should proceed immediately to the restoration of the order of deaconesses. The logistics can be worked out later, since there are more than one options: we can have deaconesses either in monasteries first and then in parishes or in certain areas, let's say urban ones, for a start and perhaps afterwards in rural regions. What needs, though, to be done here and now is a firm decision in bringing back to life an institution that will allow women’s initiatives, talents and creativity to flourish and enrich the Church’s everyday experience of the world. Most importantly, the order of deaconesses should be revived not around the gendered terms that most likely informed its establishment in the first place – i.e., having women catering for women – but in an inclusive manner that is celebratory of femininity: ordination in front of the altar, full deacon vestments and the entire range of deacon duties towards both women and men. To put it otherwise, this should not just be a restoration but a reinvention of a traditional charismatic ministry, which will affirm the differentiation of gender in the Orthodox Church, on the one hand, and overcome its past limitations, on the other.

As I have already mentioned, the prospect of having female presbyters and bishops in the Orthodox Church undermines the continuity of tradition with the past. Nevertheless, because tradition is basically and primarily a reality of the future, wherefrom the Spirit breaks in and leads the Church ‘unto the measure of the stature of the fullness of Christ’ (Eph. 4:18), the ministry of the Orthodox Church can and should be changed in terms of further diversification; besides, that’s how things have worked out in the past. In particular, women could take on new orders that would complement the ministry of presbyters and bishops; orders that could either engage more effectively with everyday worldly situations (in education, administration or finances) or cultivate the spiritual life of the Church (through counselling, fellowship or the ecclesiastical arts). Of course, this kind of development on the one hand requires a decentralisation of Church ministry that would allow bishops to focus on their spiritual/charismatic functioning as the point of reference for unity regarding all aspects of the Ecclesial Event, while on the other hand it would help in decongesting, so to speak, the everyday ministry of presbyters, who nowadays simply cannot keep up with the diverse and multiple needs of modern challenges.

The ordination of women in the Orthodox Church is not just about the restoration of tradition; it is not just about a better functioning of the whole ministry of the Church; it is not just about a proper response to the challenges of modern society in terms of changes in gender roles.

To have ordained women in the diaconate, as well as other new forms of ministry, means that the Orthodox Church will come to reflect much more lucidly its eschatological ideal of ‘neither … male nor female’ (Gal. 3:28); that the Orthodox Church will show to the rest of the Christian family what it means to uphold tradition by being faithful to it and by recreating it at once; that the Orthodox Church will prove in practice that it is truly a Church full of life, hope and vision. To be sure, what needs to be done cannot happen overnight, but it has to start from somewhere. Here the traditional order of deaconesses is the most pertinent starting point.

The faithful must be open to the voice of the Spirit, adamant in their determination, not giving in to any sort of bullying (as we saw in the case of Africa, where the Church suffered the viciousness of the Orthodox conservatives who threatened to stop funding missionary work), and full of faith, knowing that in the end the salvation of the world goes through women!

ABOUT | INSIGHTS INTO GLOBAL ORTHODOXY with Dr Vassilis Adrahtas

"Insights into Global Orthodoxy" is a weekly column that features opinion articles that on the one hand capture the pulse of global Orthodoxy from the perspective of local sensitivities, needs and/or limitations, and on the other hand delve into the local pragmatics and significance of Orthodoxy in light of global trends and prerogatives.

Dr Vassilis Adrahtas holds a PhD in Studies in Religion (USyd) and a PhD in the Sociology of Religion (Panteion. He has taught at several universities in Australia and overseas. Since 2015 he has been teaching ancient Greek Religion and Myth at the University of New South Wales and Islamic Studies at Western Sydney University. He has published ten books. He has extensive experience in the print media as editor-in-chief, and columnist, and for a while he worked as a radio producer. He lives in Sydney, Australia, his birthplace.

Δεν υπάρχουν σχόλια:

Δημοσίευση σχολίου

Σημείωση: Μόνο ένα μέλος αυτού του ιστολογίου μπορεί να αναρτήσει σχόλιο.